Kingston, 11 February 2026 – When women step into the deep sea, whether through science, governance or policy, they do not arrive alone. They carry with them the knowledge of those who came before, the aspirations of those still finding their footing and a shared responsibility to safeguard one of Earth’s last great frontiers. For Oluyemisi Oluwadare and Nezha Mejjad, two women at different stages of their scientific journeys, the deep seabed is both a place of inquiry and a space of possibility, one where experience and emergence converge. Their stories, shaped through engagement with the International Seabed Authority (ISA), reflect how capacity-building, mentorship and international collaboration can transform individual careers while strengthening collective ocean governance.

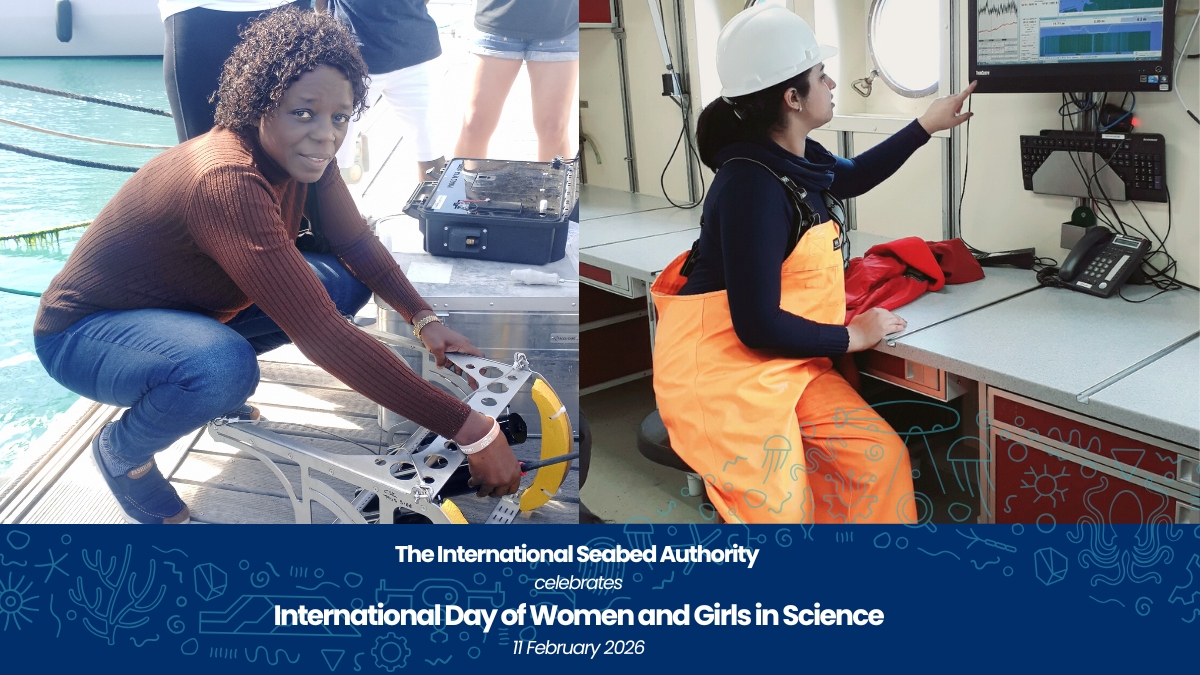

Hailing from Nigeria, the path for Oluyemisi Oluwadare into deep-sea science was neither linear nor accidental. Trained initially as an exploration geochemist and economic geologist, Oluwadare worked for over two decades with the Nigerian Geological Survey Agency (NGSA) where she supported regional geochemical mapping and delineated mineral prospectivity zones to support investment engagement, resource assessments, and subsequent exploration drilling programmes. With Oluwadare’s extensive background in terrestrial mining systems and her curiosity to expand her scientific horizon, the scale, processes, and resource potential of the deep sea presented an exciting new frontier to explore. Her formal transition into marine geoscience began with ISA’s Deep Dive Online Training Programme, where she completed all three modules consecutively, graduating in 2023. The Deep Dive offered her first structured exposure to the scientific, legal and governance dimensions of the deep seabed, from mineral resources and environmental protection to the science-policy interface that underpins international ocean governance.

“The Deep Dive programme didn’t just teach me about the deep ocean,” she reflects. “It reframed how I understood the relationship between science, regulation and global responsibility.”

That reframing became foundational in Oluwadare’s transition to shift into marine geoscience and deep-sea research. Soon after, Oluwadare was selected for ISA’s See Her Exceed Global Mentoring Programme – S.H.E., where she was paired with marine geochemist Professor Pedro Cardoso Madureira of the University of Évora, which offered her the opportunity to bridge terrestrial and marine systems, translating her expertise in mineralization processes into the context of polymetallic sulphides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts. Beyond expanding her technical skillset, developing the Gender Equity Charter with other trainees remains one of Oluwadare’s most impactful outcomes from participating in the S.H.E Programme. It reinforced her belief that scientific excellence can only be advanced when paired strong support for women’s leadership and gender inclusion.

Subsequent training through the Marine Geology Advanced Winter School in Italy organized by the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR) and supported by the International Seabed Authority Partnership Fund (ISAPF), and the BAIT training in benthic biogeological survey through the Knowledge Exchange Fellowship organized by Biosfera in conjunction with the African Network of Deep Waters Researchers (ANDR) in Cabo Verde expanded Oluwadare’s applied skill set, from geophysical interpretation to marine spatial planning to seabed habitat classification. These experiences now directly inform her work at Nigeria’s National Centre for Marine Geosciences, where she contributes to marine geological research, environmental baseline studies and science-policy advisory processes that support Nigeria’s engagement in international ocean governance.

For Oluwadare, participating in ISA’s training and mentoring programmes has been instrumental in shaping her career in deep-sea science and ocean governance, and helped her overcome barrier of underrepresentation by providing equitable access to capacity building, mentorship, and leadership opportunities. She says that ISA’s programmes allowed her to “develop strong technical and policy-relevant skills, build international professional networks, and gain confidence to contribute meaningfully to sustainable ocean governance.” As the one the leaders of the National Center for Marine Geosciences (NCMG) in Nigeria, she emphasized that “meaningful representation of women in leadership roles strengthens institutions and improves policy outcomes.”

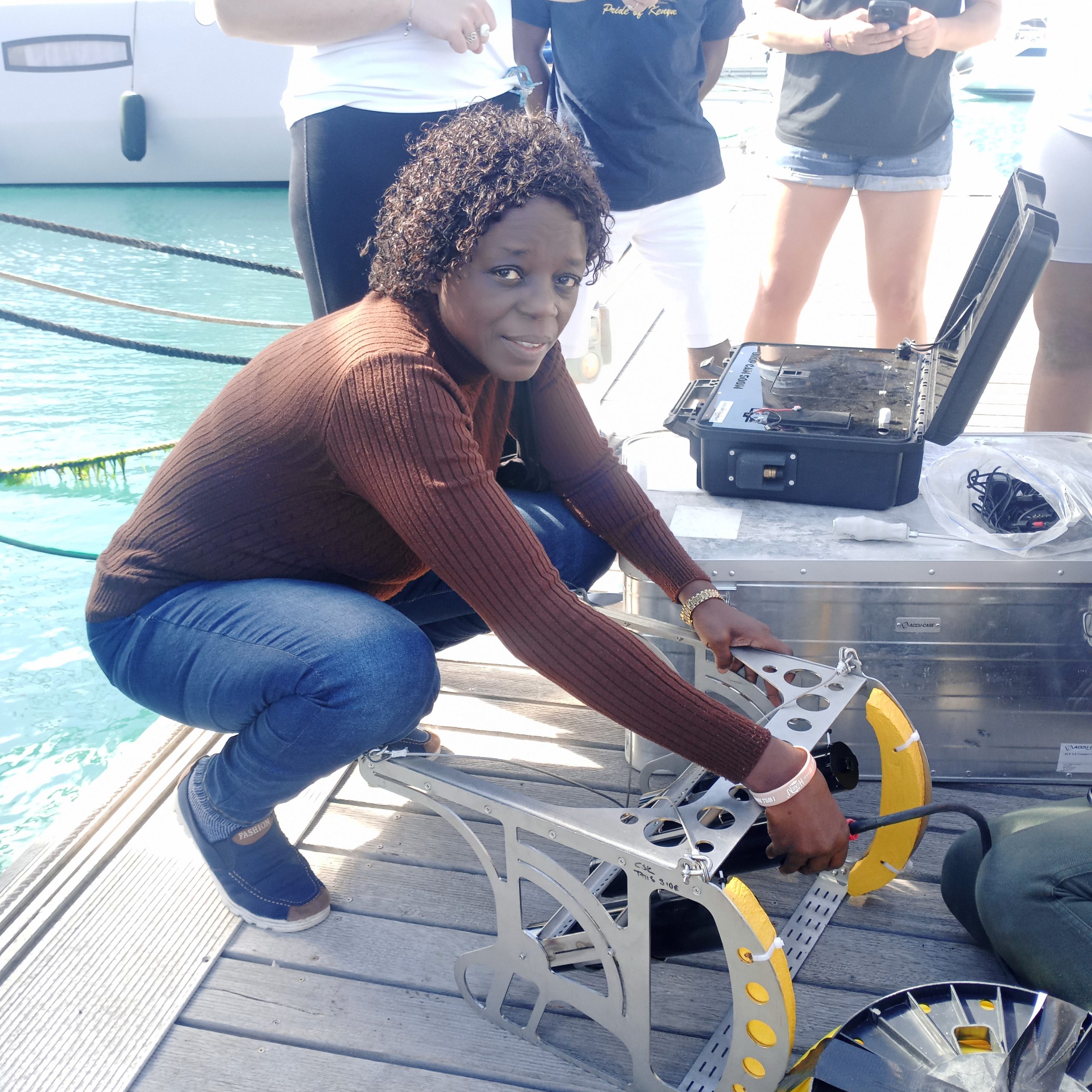

For Nezha Mejjad, an early-career scientist from Morocco, the deep sea once felt distant and defined more by knowledge gaps than by new discoveries, achievements, and endless opportunities. Her academic path had already introduced her to oceanographic research and policy analysis, including work on deep-sea mining and its implications for blue economy activities. What she sought was not just technical refinement but visibility and belonging in a field still perceived as inaccessible. Mejjad’s participation in ISA’s S.H.E. became a turning point.

“I had worked mostly with European and Arab research networks,” Mejjad explains. “The S.H.E. opened a new space for collaboration with African women scientists who share similar contexts, challenges and ambitions.”

Mentored by Dr. Marzia Rovere, Mejjad deepened her engagement with interdisciplinary research, exploring how geology, ecology, economics and governance intersect in the deep sea. More importantly, she learned how to use her knowledge effectively to overcome the invisible barrier between knowing and contributing. The S.H.E. reinforced the importance of teamwork and multidisciplinarity, skills she now recognizes as indispensable in research design, project development and policy-relevant science. It also shifted her perspective on the deep sea itself.

“So much of the narrative focuses on what we don’t know,” she says. “But through ISA, I saw how much progress is being made and how young scientists can be part of that progress.”

For Mejjad, initiatives that support women and girls in science are not symbolic gestures but structural interventions. In a field historically dominated by men, such programmes challenge assumptions, expand access and create new scientific futures. Her definition of success remains refreshingly direct: knowing how to use your capacities. And, increasingly, she is doing just that, recently publishing a technical brief with her mentor, Dr. Rovere on rare earth elements in marine sediments.

While Oluwadare and Mejjad differ in seniority and experience, their stories intersect along a single continuum: capacity-building is critical in career transition and transformation. Oluwadare’s journey illustrates how sustained engagement with ISA programmes can propel scientists into leadership roles in which science informs policy, regulation and institutional development. Mejjad’s experience shows how the same structures can empower early-career women to claim space, voice and agency within global ocean science.

Both emphasize that representation is a means to stronger governance. Women’s participation introduces diversity of thought, strengthens institutional resilience and ensures that decisions about the deep seabed reflect the realities of a shared planet.

Both also acknowledge the barriers: underrepresentation, limited access to advanced training and the need to repeatedly prove credibility. And both point to ISA’s capacity-development initiatives as a practical response offering mentorship, international exposure and professional networks that transcend geography and hierarchy.

For Oluwadare, the future lies in strengthening the science-policy interface, advancing evidence-based, inclusive governance, while mentoring the next generation across Nigeria and the African continent. For Mejjad, it lies in continued research, collaboration and contribution, transforming potential into practice.

Together, their stories underscore a simple truth: the future of deep-sea science depends on continuity between generations, disciplines and perspectives.

On the International Day of Girls and Women in Science, their journeys remind us that when women are supported to enter, grow and lead in ocean science, the benefits extend far beyond individual careers. They shape institutions. They strengthen governance. And they help ensure that the deep seabed, part of the common heritage of humankind, is explored, understood and protected for generations to come.

About the See Her Exceed Global Mentoring Programme

See Her Exceed Global Mentoring Programme – S.H.E., a flagship initiative of the Women in Deep-Sea Research project, was launched in 2023. It supports women scientists from developing countries through structured mentorship, skills development and professional networks. The pilot phase concluded in 2025, delivering knowledge outputs on marine scientific research and the safe participation of women in at-sea activities. Building on this foundation, the S.H.E. continues to promote women’s leadership and equitable participation in deep-sea research and governance.

International Seabed Authority

The International Seabed Authority is an autonomous international organization established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The International Seabed Authority is responsible for regulating mineral-related activities in the international seabed area beyond national jurisdiction. It has a mandate to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects arising from such activities.

For media inquiries, please contact:

ISA Communications Unit, news@isa.org.jm

—————

For more information, visit our website, www.isa.org.jm